The moon is quietly absorbing tiny fragments of Earth’s atmosphere — and has been doing so for billions of years, a new study reveals. This surprising case of cosmic cannibalism is thanks to supercharged solar winds and, more importantly, our own planet’s magnetic field.

The findings upend a 20-year-old theory about how certain charged particles, known as ions, ended up on the lunar surface, and could have big implications for upcoming moon missions, researchers say.

Since 2005, the leading theory suggests that this material transfer could have only happened before Earth developed its magnetic field, or magnetosphere, because this invisible forcefield would have likely trapped any atmospheric ions being blown away from our planet.

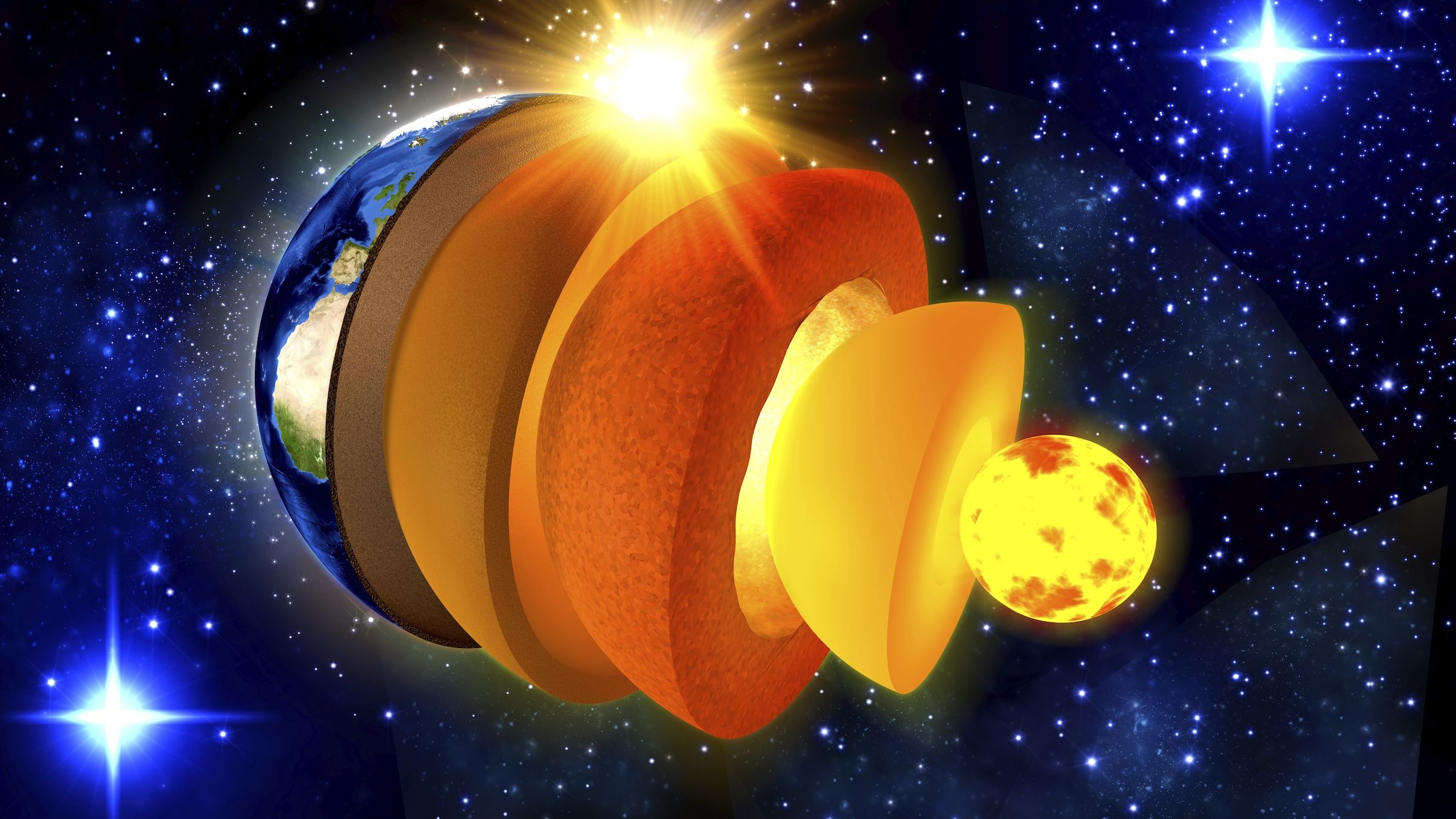

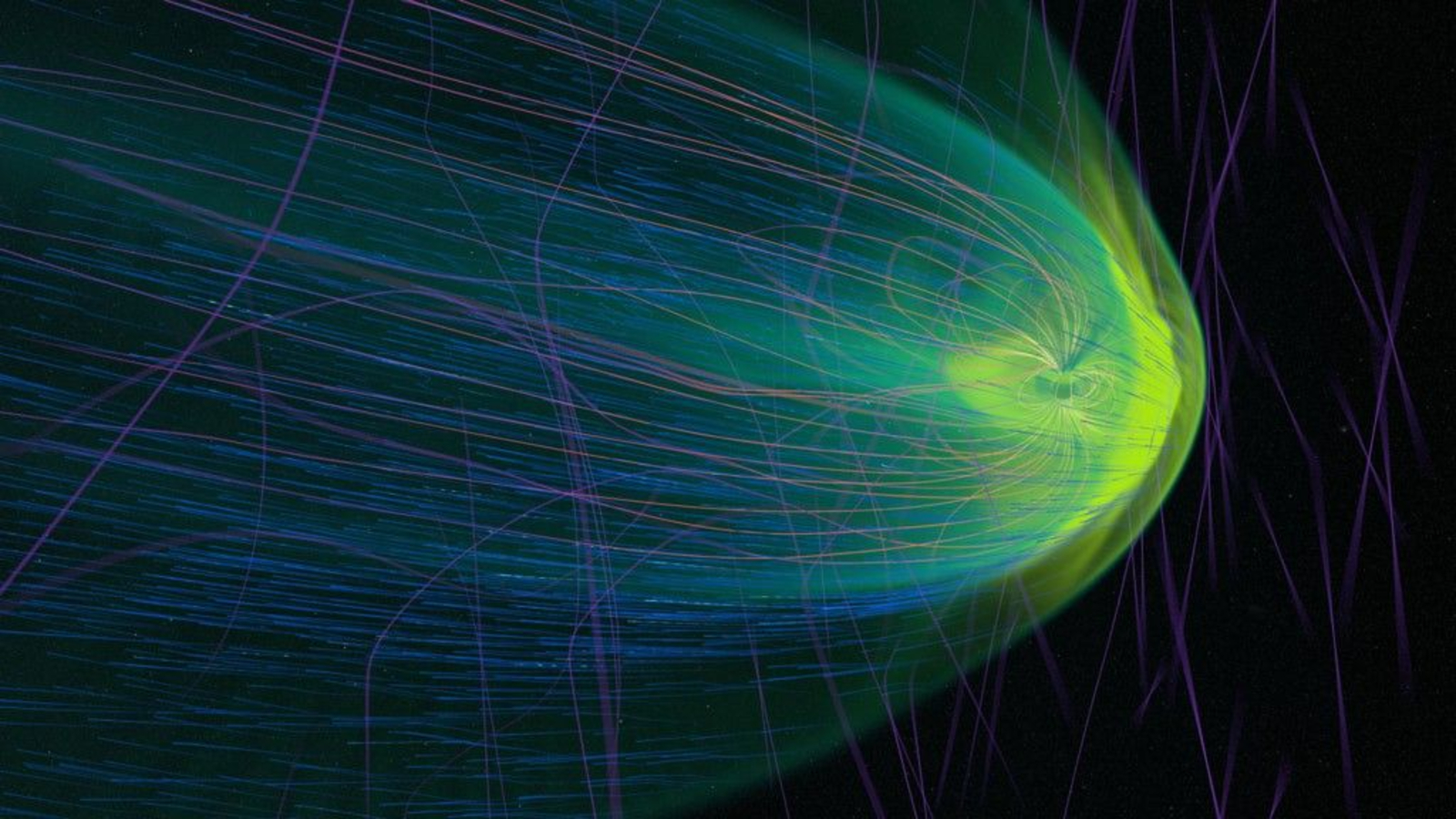

However, in the new study, published Dec. 11 in the journal Communications Earth & Environment, scientists combined data from the Apollo samples with computer models simulating the evolution of Earth’s magnetosphere, and found that the transfer of atmospheric ions was greatest whenever the moon passes through our planet’s magnetic tail — the largest section of the magnetosphere that always points away from the sun. (This alignment occurs when Earth gets between the moon and sun, near the full moon phase each month).

The models revealed that, rather than blocking atmospheric ions from being blown from our planet, the magnetic field lines within Earth’s tail act as invisible highways for charged particles, guiding them toward the moon, where they are then settled into the lunar regolith.

This means that the transfer of atmospheric ions likely began shortly after the magnetosphere took shape around 3.7 billion years ago — and is likely still occurring today.

Until now, scientists had assumed that the lunar regolith would only contain traces of Earth’s earliest atmosphere. However, the new study suggests that these samples could actually act as a time capsule for our atmosphere and magnetosphere.

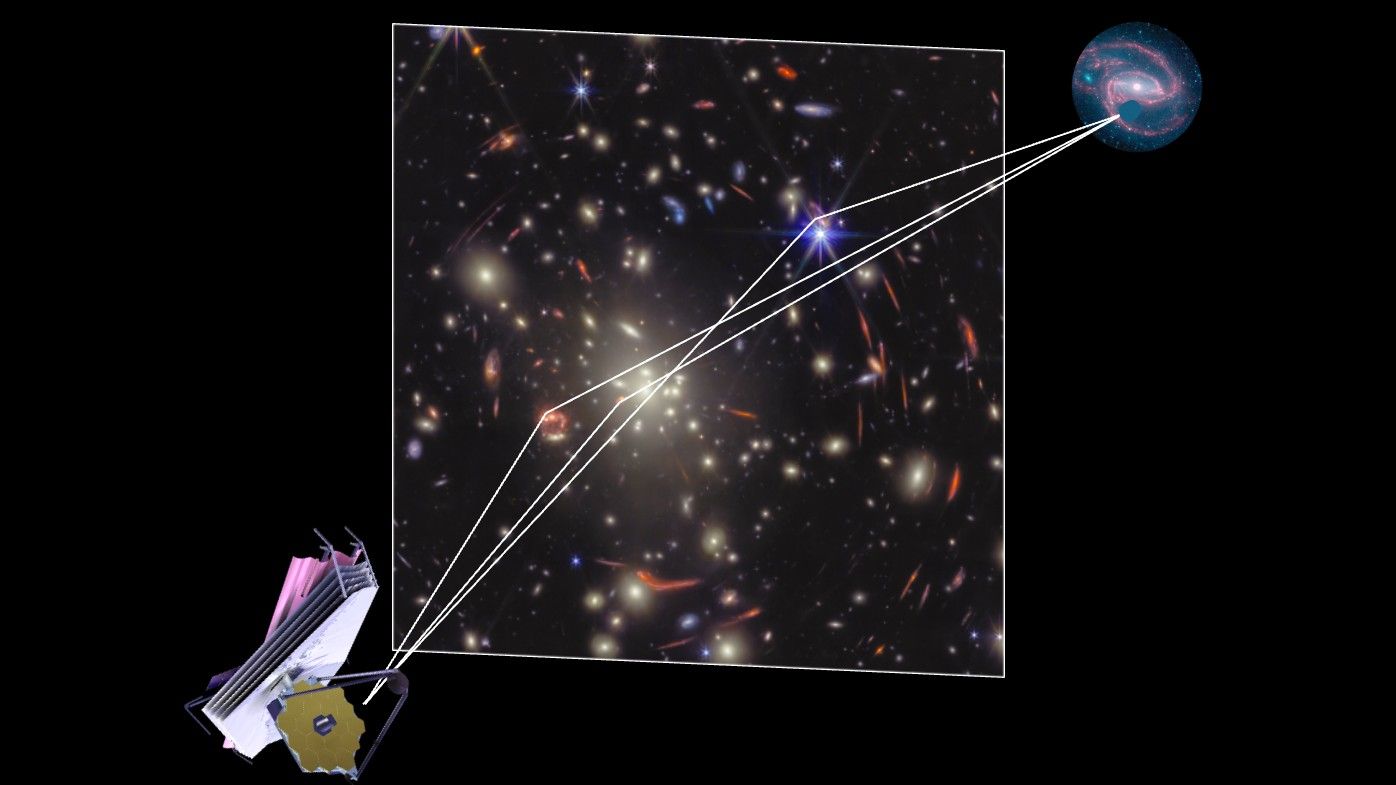

“By combining data from particles preserved in lunar soil with computational modeling of how solar wind interacts with Earth’s atmosphere, we can trace the history of Earth’s atmosphere and its magnetic field,” study co-author Eric Blackman, a theoretical astrophysicist and plasma physicist at the University of Rochester, said in a statement.

As a result, regolith collected during upcoming lunar missions — such as NASA’s Artemis program, which aims to put boots on the moon by 2028, and China’s moon missions, which have already returned lunar samples to Earth — could help researchers fill in gaps in our planet’s geological history.

Earth is not the only solar system object to lose tiny bits of itself to the solar wind. Mercury is often seen with a long comet-like tail of dust that is blown off its surface, while the moon also has a tail of ablated sodium ions that Earth repeatedly passes through.

By further studying how Earth loses its atmosphere to the moon, the researchers are hopeful of learning more about how this may have happened elsewhere in our cosmic neighborhood.

“Our study may also have broader implications for understanding early atmospheric escape on planets like Mars, which lacks a global magnetic field today but had one similar to Earth in the past,” study lead author Shubhonkar Paramanick, a planetary scientist at the University of Rochester, said in the statement. Future research could help scientists “gain insight into how these processes shape planetary habitability,” he added.