Around 1,800 years ago in Roman Britain, people preparing bodies for burial created a plaster-like paste and smeared it over the corpses, leaving behind fingerprints that are still visible today, researchers reported in a recent blog post.

These newfound prints reveal a hands-on approach to funerary practices in the third and fourth centuries A.D., the archaeologists said.

Gypsum is a calcium-based mineral that was a key ingredient in ancient plaster and cement. When heated and mixed with water, gypsum becomes a pourable liquid sometimes called plaster of paris. This thick liquid, when poured over a dead body, hardens into a plaster and leaves behind a casing or impression of the deceased, much like the casts at Pompeii.

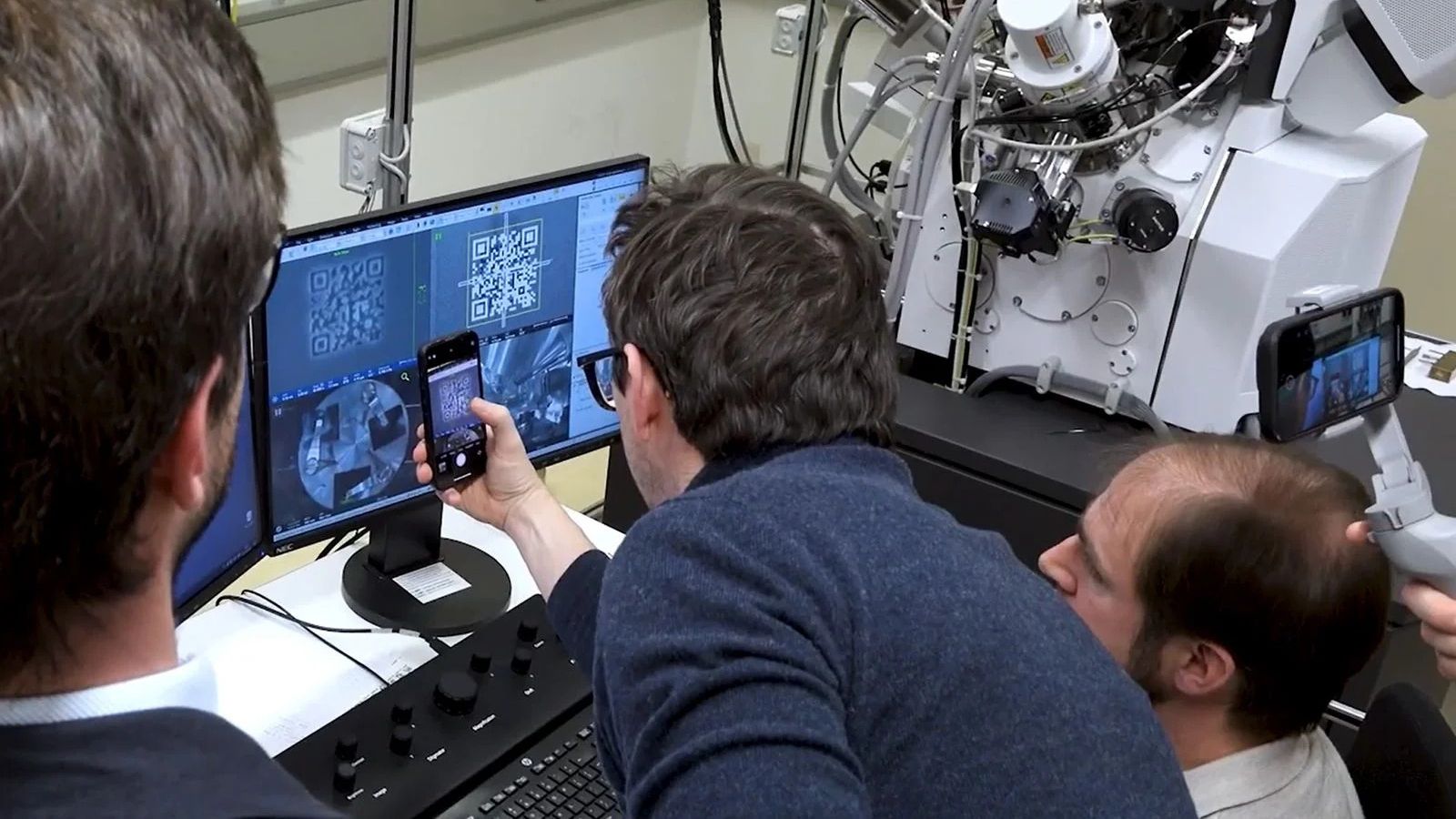

At least 45 liquid gypsum burials have been discovered in the Yorkshire area to date. When investigating one of them — a stone sarcophagus found in the 1870s that had not been properly studied before — the team found a surprising clue to the method of applying the liquid gypsum: Someone had spread it by hand.

“When we lifted the casing and began cleaning and 3D scanning, we discovered the hand print with fingers and were astounded,” Maureen Carroll, a Roman archaeologist at the University of York and principal investigator of the Seeing the Dead project, told Live Science in an email. “They had not been seen ever before, nor had anyone ever removed the casing from the sarcophagus.”

In a Dec. 10 blog post, Carroll explained that the team had previously assumed the liquid gypsum was heated to at least 300 degrees Fahrenheit (150 degrees Celsius) and poured over the body. But the presence of fingerprints means that the gypsum mixture was probably a soft paste that someone smoothed over the body in the coffin. The gypsum had been spread very close to the edges of the coffin, so the fingerprints were not visible until the team removed the casing from the coffin.

The fingerprints and hand marks reveal the close, personal contact the Romans had with their dead, according to Carroll. “They are a striking trace of human activity that is not otherwise known to survive on a body in a Roman funerary context,” she wrote in the blog post.

The marks might preserve additional clues about the person or people who buried the dead — revealing, for example, whether a professional undertaker or a family member last touched the deceased.

“We are hoping to extract potential DNA remains from the handprint for examination at the Francis Crick Institute in London,” Carroll said. It’s a long shot, but “the best case scenario is that we may be able to infer genetic sex, which would be a huge result!”