An ambitious new survey by the Hubble Space Telescope provides the first-ever bird’s-eye view of all known dwarf galaxies orbiting the Andromeda galaxy.

The results reveal that over billions of years, Andromeda and its family of dwarf galaxies have experienced markedly chaotic interactions — like a game of bumper cars — compared with the relatively placid evolution of the galaxies circling the Milky Way.

The findings, published in The Astrophysical Journal, demonstrate that we may not be able to extrapolate information about other galaxies from our understanding of our own galaxy, the study authors said.

“There’s always been concerns about whether what we are learning in the Milky Way applies more broadly to other galaxies,” study co-author Daniel Weisz, an associate professor of astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement. “Our work has shown that low-mass galaxies in other ecosystems have followed different evolutionary paths than what we know from the Milky Way satellite galaxies.”

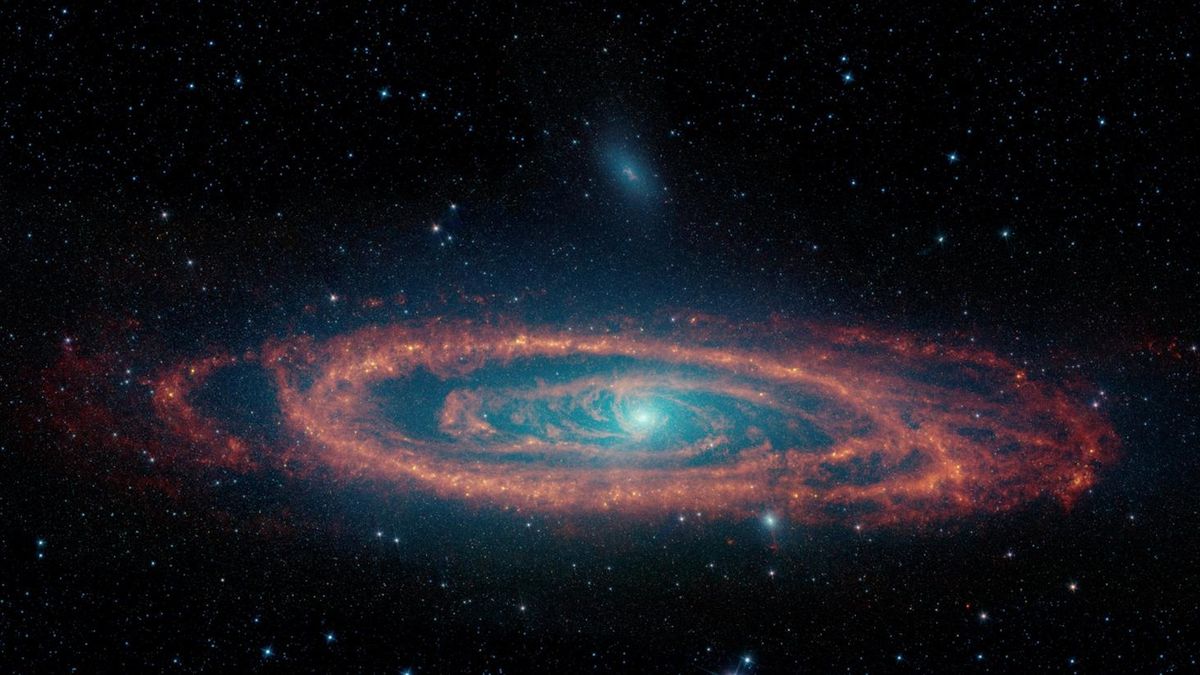

At about 2.5 million light-years away, Andromeda is the closest major galaxy to our own, and getting closer; Andromeda and the Milky Way are predicted to collide and merge in about 5 billion years time. To the naked eye, it appears as a faint, spindle-shaped object that covers about the same amount of sky as the full moon. What isn’t visible without powerful telescopes and is not well studied is the swarm of three dozen smaller galaxies scattered around Andromeda, like bees around a hive.

Related: The Andromeda Galaxy glows rosy red in gorgeous new Hubble Telescope image

Starting in late 2019, Hubble spent two years cataloging images — as well as measurements of the locations and motions — of three dozen galaxies swirling up to 1.63 million light-years from Andromeda. These data provided Weisz and his team the first comprehensive 3D map of our galactic neighbor’s ecosystem. Using this information, the researchers studied the processes that drove the evolution of these dwarf galaxies over nearly 14 billion years of cosmic time.

“Everything scattered in the Andromeda system is very asymmetric and perturbed,” Weisz, principal investigator of this Hubble program, said in the statement. “It does appear that something significant happened not too long ago.”

That something, the researchers posit, was a collision between Andromeda and a large galaxy a few billion years ago. The possible culprit could be Messier 32, a satellite galaxy of Andromeda and its brightest companion. Astronomers suspect that M32, which is visible to Andromeda’s bottom left, is the remnant core from the merger.

“No one knows what to make of that”

Analysis of the Hubble observations also revealed a unique population of galaxies around Andromeda that has not been observed around the Milky Way, according to the new study.

This group began forming most of its stars early on and continued to do so at extremely low rates and for much longer than astronomers would expect. Given the intense gravitational pull of Andromeda, these galaxies should have been stripped of their star-forming gas long ago, similar to what is observed around the Milky Way.

“This doesn’t appear in computer simulations,” study lead author Alessandro Savino, an astrophysicist at the University of California, Berkeley, said in the same statement. “No one knows what to make of that so far.”

The survey also revealed that half of Andromeda’s dwarf galaxies orbit in a unique, flat plane, all moving in the same direction — a configuration not observed around other galaxies, including our own.

“That’s weird,” Weisz said in the statement. “It was actually a total surprise to find the satellites in that configuration and we still don’t fully understand why they appear that way.”

The galaxies assembled into the “Great Plane of Andromeda” don’t exhibit distinguishable traits, such as patterns in star formation. This suggests the plane is not a physically distinct structure but rather a serendipitous configuration whose origins are not yet fully understood, the researchers say.

“There is a lot of diversity that needs to be explained in the Andromeda satellite system,” Weisz said in the statement. “The way things come together matters a lot in understanding this galaxy’s history.”