An undersea volcano off Oregon’s coast will probably erupt in 2025, scientists say.

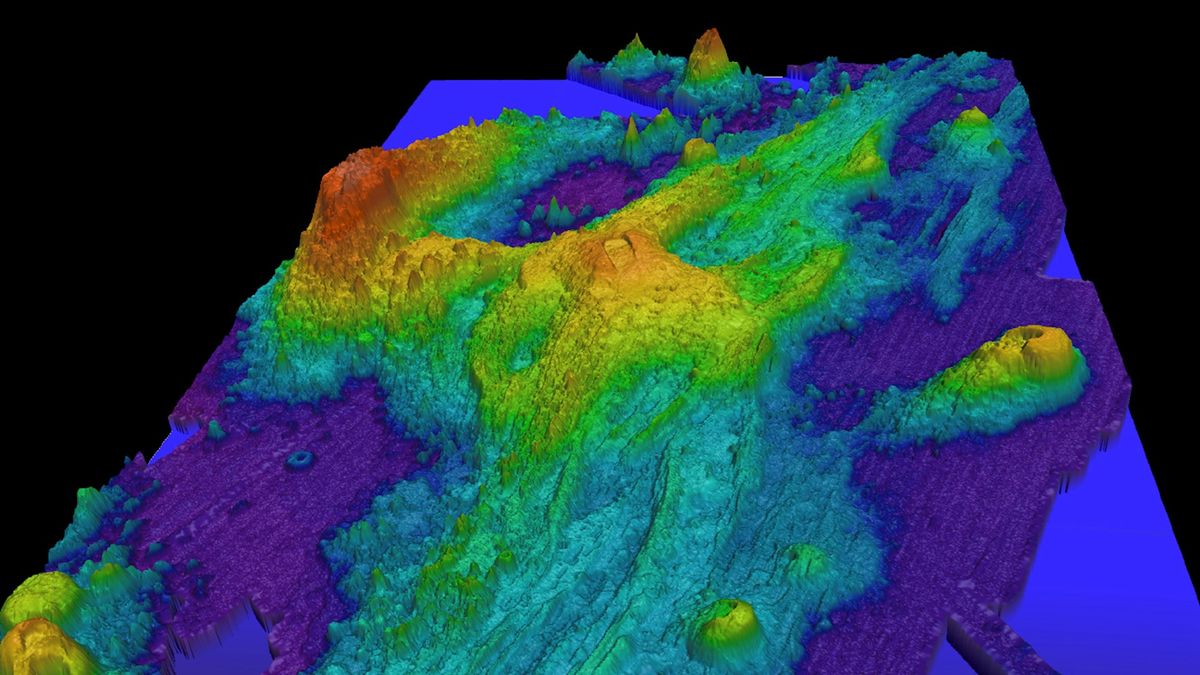

The volcano, known as Axial, is a seamount 300 miles (480 kilometers) west of Cannon Beach, Oregon. The Axial seamount erupts regularly — it rumbled to life in 1998, 2011 and 2015, according to a blog by scientists monitoring the seamount — and it doesn’t pose a threat to people. But because of the seamount’s regular activity and its relative proximity to land, researchers made it the site of the world’s first underwater volcano observatory, known as the New Millennium Observatory.

Now, the monitors at Axial are showing that the surface of the seamount is inflating — a sign of moving magma that likely presages an eruption, William Chadwick, a geologist at Oregon State University who studies the volcano and its nearby hydrothermal vents, reported at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in December 2024. The volcano’s surface has now risen to 95% of what it was before the 2015 eruption, Chadwick reported.

The activity follows a period of quiet between 2015 to 2023, during which the seamount barely budged. The new rise began in the fall of 2023 and increased in January 2024, with the ground moving upward at a rate of about 10 inches (25 centimeters) per year as of mid-2024. This inflation was accompanied by swarms of hundreds of small earthquakes. Since then, the inflation rate has stabilized, Chadwick reported in his blog.

“The rate of inflation at Axial has been steady for the last 6 months and the rate of seismicity has moderated,” he wrote. “An eruption does not seem imminent, but it can’t do this forever.”

He and his co-author Scott Nooner, a geophysicist at the University of North Carolina Wilmington suspect that the volcano will erupt before the end of 2025.

The scientists are hopeful that their prediction is correct, because the well-monitored Axial is a promising location to work out the patterns a volcano experiences before eruption. The fact that the volcano has recently erupted several times over two decades – rather than once in centuries, like many volcanoes – makes discerning patterns easier. Researchers are also more comfortable offering tentative predictions for a volcano that doesn’t threaten life or property, because there are no downsides to being wrong. Volcanologists can currently make accurate short-term predictions of eruptions, but according to the Smithsonian Global Volcanism Program, predictions are rarely reliable more than a few days in advance.

“There’s no crystal ball,” Valerio Acocella, a volcanologist at Roma Tre University in Rome who wasn’t involved in the research told Science News. A volcano could always switch up its habits. But making predictions based on a well-monitored volcano and trying to understand how the surface activity of the volcano reflects the movements of magma and fluids underneath could help researchers make longer-term predictions at volcanoes around the world.

“We need these ideal cases to understand how volcanoes work,” Acocella said.