Since the 1990s, doctors have prescribed the drug metformin to treat type 2 diabetes, but scientists didn’t fully understand how it worked.

Now, new research fills in one piece of the puzzle: Metformin triggers the body to expel glucose from the bloodstream into the intestines, where bacteria feed on the carbohydrate to make compounds that may help control blood sugar levels.

In the new study, published March 3 in the journal Communications Medicine, researchers calculated that metformin treatment increased how much glucose was released into the gut nearly fourfold. That seemed to boost the production of fatty compounds that help protect the gut and reduce inflammation.

Multiple pathways

Most research has focused on metformin’s effects in the liver, where it boosts how cells respond to insulin and blocks the synthesis of the sugar glucose. But some studies have suggested that the drug also acts on the gut, perhaps by blocking glucose uptake into the bloodstream.

“Many people are working on the gut action of metformin because if you take metformin orally, the intestines are exposed to very high concentrations,” said senior study author Dr. Wataru Ogawa, a medical researcher at Kobe University in Japan. (Ogawa received research support and lecture fees from the metformin manufacturer Sumitomo Pharma.)

Previously, Ogawa’s team showed that the body excretes glucose into the hollow tunnel of the human gut where food and waste travel, known as the lumen. This happens in people with and without diabetes. “It means that this is a physiological function that humans have,” Ogawa told Live Science.

Related: Ozempic-style drugs tied to more than 60 health benefits and risks in biggest study-of-its-kind

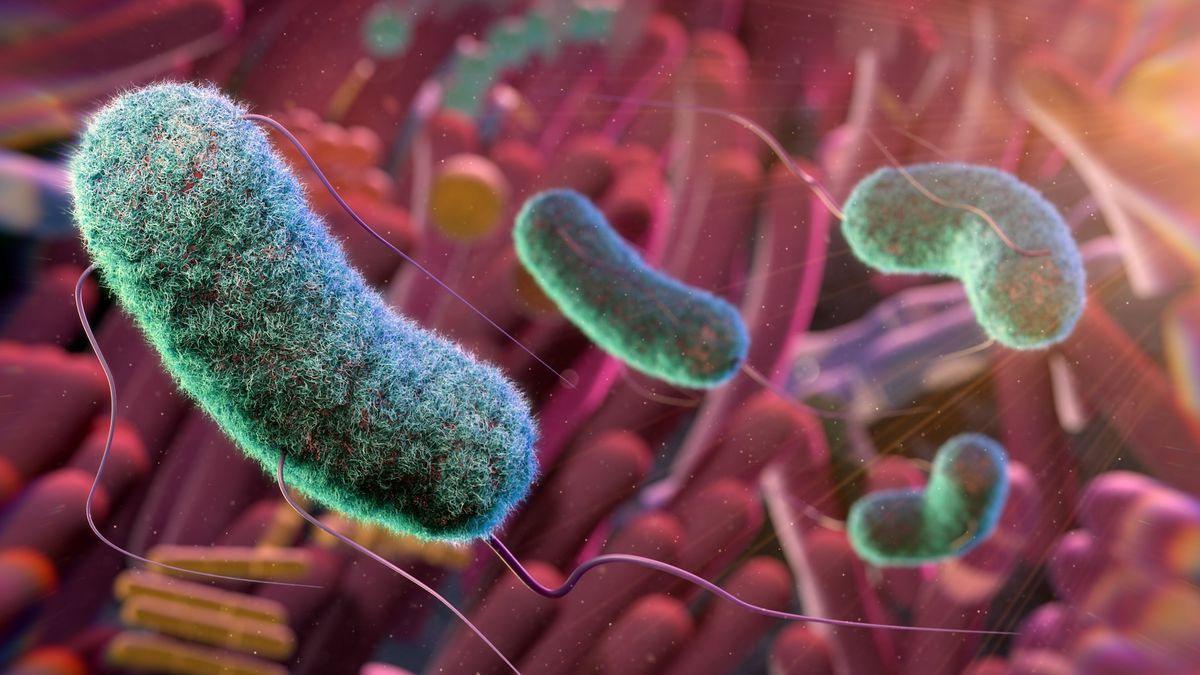

Feeding gut bacteria

In the new study, the researchers found that metformin nearly quadrupled the rate of glucose excretion into the gut in five people with type 2 diabetes, and they replicated those findings in mice.

Keeping glucose out of circulation by directing it to the gut might directly lower blood sugar levels, but scientists told Live Science they think this explains only part of metformin’s therapeutic effects.

Nicola Morrice, a metformin researcher at the University of Dundee in Scotland who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email, “I do not expect this to be the drug’s main mechanism of action.”

Besides drawing sugar out of the bloodstream, excreted glucose could also have an indirect effect on blood sugar by feeding gut bacteria, other experts told Live Science.

Dr. José-Manuel Fernández-Real, a medical researcher at the University of Girona in Spain who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email, “Some bacteria, particularly those that thrive on simple sugars, may experience increased growth, while others that rely on complex carbohydrates or fiber fermentation might be less affected.”

A glucose molecule has a backbone of six carbon atoms, so to determine the rate at which gut bacteria break down glucose into other molecules, Ogawa had to find a way to keep track of these carbons. His team injected mice with glucose containing a “heavy” isotope, meaning a version of carbon that carries an extra neutron. This allowed them to trace the heavy carbons as the bacteria transformed glucose into other compounds.

Stool samples revealed that bacteria in mice treated with metformin had converted the heavy glucose into short chain fatty acids (SCFAs). “Bacterial species that produce short chain fatty acids are generally ‘good’ bacteria,” suggesting metformin’s effects could potentially foster a healthy microbiome, Ogawa said.

Metformin treatment caused SCFAs containing heavy carbon to increase by just 1% in stool samples. However, Manuel Vázquez-Carrera, a pharmacology researcher at the University of Barcelona who was not involved with the study, told Live Science in an email that “most SCFAs are rapidly absorbed and utilized rather than excreted.” That means the measurement was likely an underestimate.

And “even a slight rise in SCFA production could enhance gut barrier function, reduce inflammation, and improve insulin sensitivity, all of which are beneficial for managing diabetes,” Fernández-Real speculated.

The study had a few limitations. First, the researchers did not assess how higher levels of gut SCFAs affected the health of the mice. It also included “a very small number of participants who were receiving varying doses of metformin as part of their treatment regimes,” Morrice said.

The mouse work also involved only male rodents, so possible sex differences in the drug’s actions were not explored. Beyond testing metformin’s effects on five diabetes patients, Ogawa said he has finished a larger, gold-standard trial in humans to further study the drug’s impacts on the gut. The researchers haven’t completed the analysis, but as of yet, they haven’t seen any sex differences.

Morrice suggested that future work could explore how metformin affects glucose excretion in mice that consume different diets, such as high-fat, high-sugar diets, which are linked to obesity.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.